During on my final stage interview at PRIA, I was fortunate enough to engage in discussion with Rajesh Tandon Sir, on a recurring observation of mine on how policies and studies are often designed remotely, with researchers comfortably stationed in cities like Delhi, Mumbai, or Bangalore, far removed from the very communities they aim to ‘support’. I couldn't help but reflect on my own experiences, where I had conducted studies and formulated proposals solely from the confines of my desk. Surprisingly, some of these endeavors were even ‘successful’, despite my lack of firsthand knowledge about the ground realities.

In many of my previous research undertakings, the focus primarily revolved around numbers and questionnaire-based surveys, as dictated by the organizations I used to work for, one of my previous superiors even went so far as to emphasize that only numbers truly mattered. While these surveys did provide numerical data, they seemed to overlook the rich narratives behind the statistics. Even though these surveys did give us numbers, it missed narratives and towards the end of it we felt that participants often lost interest. However, my encounter with participatory research brought about a strikingly different perspective. I discovered that people became significantly more involved, from the initial stages to the very end, compared to conventional quantitative based surveys. Additionally, the inclusion of narratives and the ability to delve deep into the root causes of problems allowed for a comprehensive understanding, provided the facilitator could effectively engage with stakeholders.

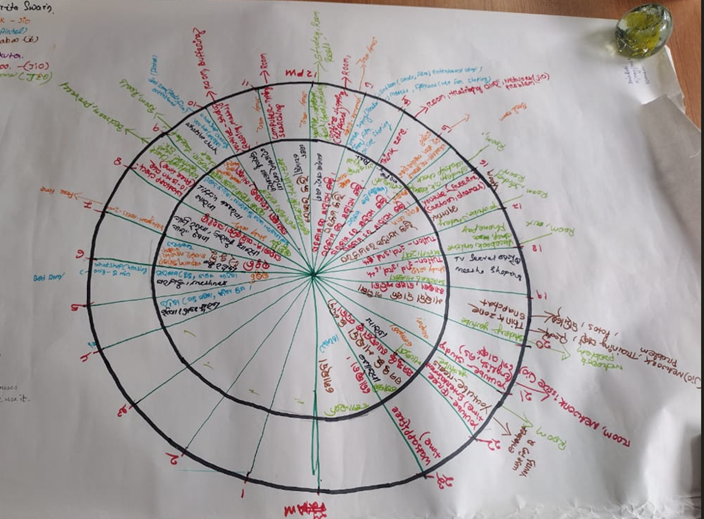

Image 1: A group of participants engaged in Daily Activity Clock

It was during the months of May and June 2023 that my colleague, Meghna, and I embarked on a field visit to both rural and urban areas of Odisha. This particular field visit differed remarkably from my previous forays into the field. Not only was it my first experience working in the domain of gender and digital trust, but it was also my introduction to Participatory Vulnerability Assessment (PVA) tools. What transpired during this journey was truly captivating, as the participatory activities we employed evoked powerful emotions among the participants. It was through these experiences that I came to appreciate the transformative power of participatory research, recognizing its potential to foster deep understanding, shape effective studies, and truly engage with the community.

In Ganjam district, Odisha, we conducted an activity called the Digital Yatra, in which adolescent girls were encouraged to map their digital journeys as milestones on a road. During this endeavor, I noticed that one of the girls hesitated to write or illustrate anything on her sheet of paper. Sensing her reluctance, I approached her and inquired about her reservations. Her response was heartrending: "Sir, I don't have a phone, nor does anyone in my family own one." As she revealed this, her eyes welled up almost with tears. Another participant shared a poignant story about how her mother, in the past, used to narrate stories and encourage her and other children to gaze at the moon while eating, so that the child looks at the moon and eats her dinner. This seemingly ordinary practice fostered a sense of togetherness and nourishment. However, with the advent of smartphones, the mother now urged her child to divert attention to the screen, effectively eradicating the cherished dinner stories of yore.

Image 2: The completed version of the Daily Activity Clock

To gain further insights into the daily routines and mobile usage patterns, we conducted a daily digital activity clock with both rural men and women. The results were striking. Women, whether working or tending to household chores, found themselves engrossed in their domestic responsibilities, leaving little time for phone usage. Conversely, the men in the community, according to the result of our activity, primarily focused on farm work, sparing them ample time for digital applications and they don’t undertake any domestic chores. When we posed a question to a group of male government officers about whether the women in their families spent more time using smartphones than them, their unanimous and joyous response was an emphatic "Yes." Laughter filled the air as they said this. However, this perception contradicted the result of our studies. But when I reached back while analyzing the data, I thought what if these officers were right in their case as these officers come from privileged socio-economic backgrounds, whose spouses could hire help for domestic chores? Another common thread that emerged across all areas was the imposition of social taboos on women's phone usage. Excessive phone use was often equated with a woman's character, potentially tarnishing the family's honor. Strikingly, the only group exempt from this restriction was the transgender community. Unencumbered by societal constraints, they exhibited a more proactive approach toward smartphone usage than any other groups.

While numbers undoubtedly hold significance, enabling us to quantify problems, measure impacts, make informed decisions, communicate results, and build consensus, they often fail to convey the complete narrative surrounding an issue. Sometimes numbers tend to oversimplify complex problems and can create false impressions regarding the scale and scope of the challenges at hand. This is precisely where participatory research emerges as a valuable tool, bridging these gaps and providing a holistic understanding that numbers alone cannot encapsulate.

My journey into participatory research has been nothing short of enlightening. It has enabled me to recognize the power of engaging with communities, understanding their needs, and amplifying their voices. Through the anecdotes, experiences, and emotional revelations shared by participants, I have come to appreciate the multifaceted nature of research, extending far beyond the confines of numerical data. Participatory research, with its emphasis on inclusivity, narratives, and contextual understanding, has the potential to reshape our approach to problem-solving and facilitate meaningful change.

Ms. Meghna Sandhir, along with our team members, has been engaged in the Drivers, Limiters, and Barriers to Women's Trust in Digital Platforms Project since last year. She is blogging about her firsthand experiences from visiting our project sites in India.

Ms. Aashini Goyal, along with our team, has been working on the Drivers, Limiters, and Barriers to Women's Trust in Digital Platforms Project for the past two months. This blog recounts her firsthand experiences from visiting our project site in India.

Ms. Meghna Sandhir, our programme officer, along with colleagues from Martha Farrell Foundation and Pro Sport Development, participated in the Trainers of Training (ToT) program conducted at Sahbhagi Shikshan Kendra - SSK Lucknow. The training took place from December 4th to December 10th, 2023.